February 11th is widely recognized as the International Day of Women and Girls in Science. This holiday promotes equal access for women and girls in scientific fields and acknowledges the important contributions and innovations of female scientists.

Strong representation and frequent positive role models are integral to building self-confidence and a sense of belonging in science. Studies show that many young girls often lose confidence in math as early as third grade (Lewis and Schindler 637). Throughout their undergraduate careers, female students are significantly underrepresented in STEM majors, with women making up just 21% of the engineering field (“Women in STEM: Statistics, Progress, and Challenges”).

In observance of the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, let’s look at some incredibly impactful women who helped to shape science as we know it:

Ada Lovelace – Born in 1815 to mathematician Annabella Milbanke and her poet husband, Lord Byron, Augusta Ada King, known as Ada Lovelace, learned mathematics from an early age. She was especially captivated by machines and inspired by the innovations of the industrial revolution. Her mother insisted that she study mathematics, an unusual pursuit for a woman at this time.

In 1833, Ada met Charles Babbage, a mathematician and inventor who would become an impactful mentor. While Babbage is known as the “Father of Computers” and credited with the invention of the first automatic digital computer, (the Analytical Engine), Ada Lovelace hypothesized that the computer could be programmed to follow specific instructions. She was asked to translate Babbage’s article on the Analytical Engine in 1842, and Babbage also requested that she expand it with her own understanding of the machine. Her revised article was over three times the length of the original, containing new insights that influenced the future of computer engineering.

Image: The New Yorker

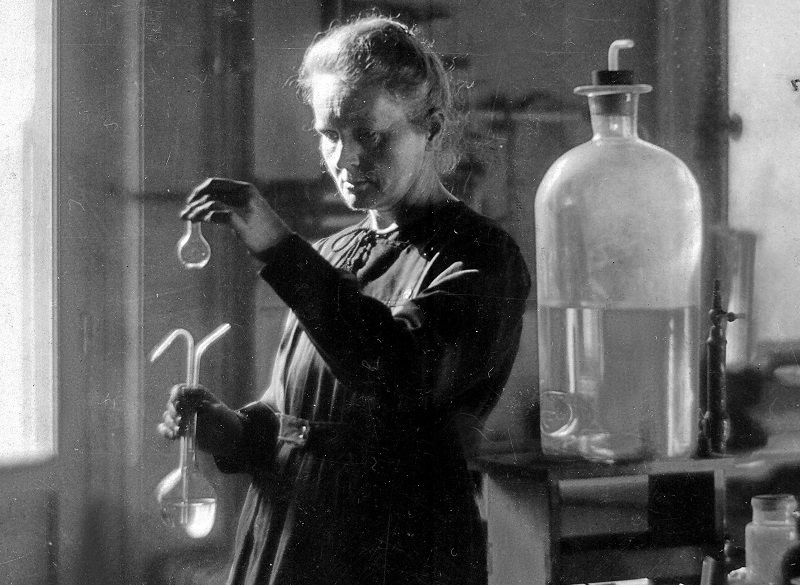

Marie Curie – As the first woman to receive a Nobel Prize (Physics, 1903; Chemistry, 1911) Dr. Marie Curie is widely known for her research in radioactivity that led to developments in cancer treatments and isolation of the elements radium and polonium.

Marie Curie’s academic accomplishments led her to study at the Sorbonne in Paris, where she also taught, and to become the director of the Curie Laboratory in the University of Paris’s Radium Institute. However, since women were not permitted to attend university in her home city of Warsaw, Poland, Curie attended a “Flying University,” which secretly educated women across various locations and allowed Curie to begin her scientific training. Before leaving Poland, she was also involved in a students’ revolutionary organization that promoted Polish independence and resisted educational barriers.

Curie’s scientific career began under difficult educational and laboratory conditions, but she ultimately rose to become one of the world’s most esteemed scientific minds.

Image: Smithsonian Magazine

Elizabeth Blackwell – Born in 1821, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell was raised by a family of activists. After moving from England to America, she became a teacher in order to aid her family during a period of financial instability. After a conversation with a friend who acknowledged the importance of female physicians, Blackwell became inspired to pursue medicine. However, since no medical colleges accepted women at the time, she received rejection after rejection until she received one acceptance from Geneva Medical College. Though this was intended as a joke, Blackwell took full advantage of the opportunity. She faced discrimination in school and was often excluded from lectures and labs on the basis of gender. Even in hospital training, she was instructed to do different jobs than any of the men. Despite this, she sought to solve issues facing medicine at the time, including lack of personal hygiene and lack of emphasis on preventative care.

She later returned to New York City, where she continued to face challenges but was able to open a small clinic to help low-income women and provide opportunities for female physicians to train. As a true problem-solver, Blackwell went on to open a medical college in New York. After leaving New York, she became a professor of gynecology at the newly-founded London School of Medicine for Women. She helped to establish the National Health Society, and in 1895 she published her autobiography, Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women. Elizabeth Blackwell remains a prime example of resilience and a role model to female physicians across the world.

Image: National Women’s History Museum

Janaki Ammal – Dr. Janaki Ammal was not only India’s first female botanist, but also the first woman to receive a doctorate degree in botany in the U.S in 1913. During a time when India’s literacy rate for women was about one percent, she valued her education over what society expected of her, as women were discouraged from higher education both nationally and internationally. Her work at the University of Michigan during the 1920s allowed her to study plant hybrids and develop sugarcane species that were suited to India’s climate, which helped with food shortages and preservation of indigenous ecosystems subjected to deforestation. She made significant impacts as a plant-scientist and advocate for protection of India’s native plant species, and her work is commemorated by two flower species, a type of magnolia and a hybrid yellow rose, named for Dr. Janaki Ammal.

Image: Association for Women in Science

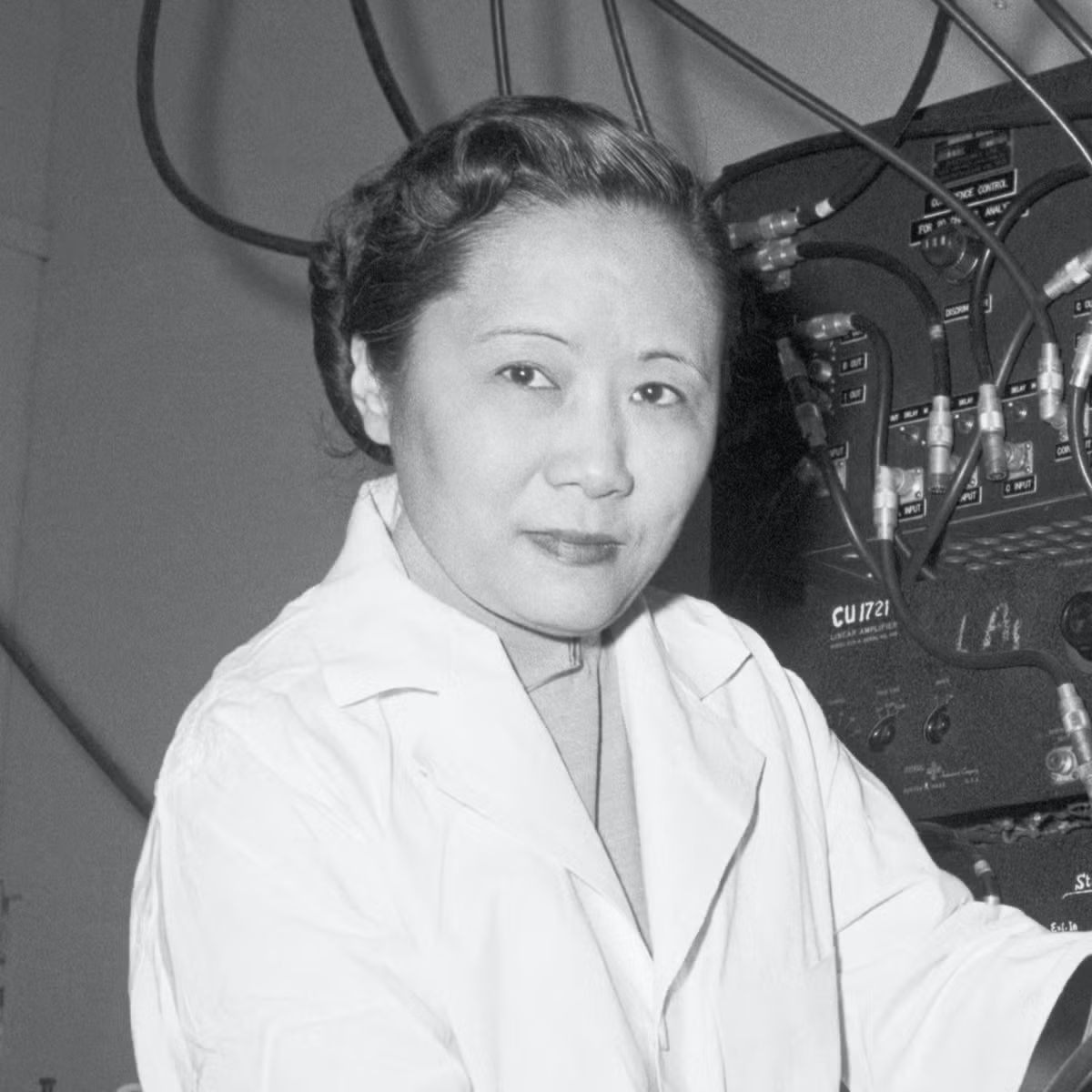

Chien-Shiung Wu – Dr. Chien-Shiung Wu, “the First Lady of Physics,” grew up in China attending a school founded by her father, who strongly believed that women should receive education. She had a very successful academic career, graduating at the top of her class and matriculating to Nanjing University to study physics. She later worked in a lab in China, but was encouraged by her mentor, Dr. Jing-Wei Gu, to pursue her work in the U.S. After earning a PhD from the University of California, Berkeley, she and her husband moved to the East Coast, where she became the Princeton University Physics Department’s first female faculty member.

She eventually continued her work in physics at Columbia University and became involved with the Manhattan Project, where she conducted uranium research.

After World War II, she continued at Columbia University, where she conducted experiments that confirmed Fermi’s Theory of Beta Decay. She worked with physicists Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang to test other theories of beta decay, which became known as the Wu experiment. Despite this, when Yang and Lee won a Nobel Prize, Dr. Wu was not included.

Her leadership in physics inspired many women at the time, and her research crossed into other fields such as medicine. She was acknowledged with awards, but still saw the disparities that academic women faced. She used her scientific platform to bring awareness to these inequalities, asking, “whether the tiny atoms and nuclei, or the mathematical symbols, or the DNA molecules have any preference for either masculine or feminine treatment.”

Image: Getty Images

Katherine Johnson – Katherine Johnson, a star student growing up, left her teaching position to join a graduate program in mathematics after being one of few African American students offered spots at West Virginia University. At the Langley Laboratory of the NACA (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, she worked in the “computing” section for flight research and secured a permanent position. According to Johnson, she was a computer, “when the computer wore a skirt.”

The Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik revolutionized space travel and sent the NACA, later known as NASA, into an era of developments in space exploration, which Katherine Johnson was part of. She published analyses and research reports for countless missions including Alan Shepard’s spaceflight, the first American human spaceflight. John Glenn would only fly in his 1962 orbital mission if Johnson checked the numbers first. Johnson’s work played an integral role in some of NASA’s most influential advancements, including Project Apollo’s Lunar Module, the Space Shuttle, and the Landsat satellite. In 2015, at age 97, she was honored with the Presidential Medal of Freedom

Image: NASA

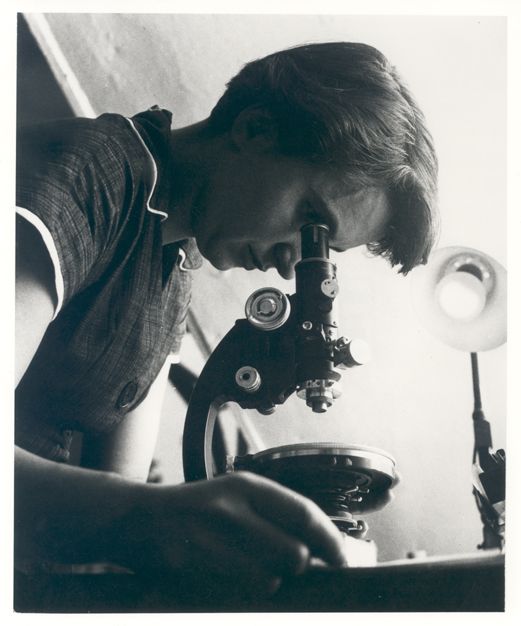

Rosalind Franklin – Rosalind Franklin captured “Photograph 51” in 1952, revealing DNA’s helical structure that contributed to the genetic development of all living organisms. Her notes showed knowledge on DNA’s structure and discussed its A and B forms. However, her role in the discovery of DNA is often overlooked and accredited entirely to scientists Watson and Crick, who dismissed Franklin’s expertise as a crystallographer.

Rosalind Franklin had worked at King’s College since 1951 on a fellowship where she studied changes in protein solutions. Her work later shifted towards DNA research, where she worked with PhD student Raymond Gosling to construct a microcamera for diffraction images of DNA. After months of work, they suspended DNA and captured the historic “Photograph 51” with an X-ray beam and over one-hundred hours of exposure. Although not acknowledged in publications by Watson and Crick, Franklin’s work opened the door to the future of biology research and left behind a legacy of scientific dedication.

Image: MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology

Vera Rubin –

“Science is competitive, aggressive, demanding. It is also imaginative, inspiring, uplifting. You can do it, too. … Each one of you can change the world, for you are made of star stuff, and you are connected to the universe.” – Dr. Vera Rubin

Vera Rubin pursued her interest in space exploration from a young age. Inspired by the first U.S female astronomer Maria Mitchell, who taught at Vassar College, she attended Vassar College for astronomy (she was the only female student in the program) after graduating high school in 1944. She conducted research at the Naval Research Laboratory and the U.S Naval Observatory during her summer breaks, beginning a fruitful research career, where she completed her graduate degrees and spent decades teaching at universities. Near her final year of teaching, she eagerly accepted an invitation to observe from the Palomar Observatory in San Diego, California, where women were typically prohibited from using the 200-inch telescope, and continued to pave the way in astronomical research. In Washington D.C, she became the first female scientist at the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Terrestrial Magnetism. While much of her work was ignored, astronomer Kent Ford took interest in it, and the two of them began working together.

One of Rubin’s most defining discoveries took place later on, when she contributed to evidence supporting the existence of elusive dark matter and its impact on the structure of the universe. Rubin and Ford published nine papers together and compiled data on the rotations of galaxies, where they noticed phenomena that defied current understandings of physics. Their evidence turned a historically overlooked theory into a convincing one. In the following decades, scientists learned that dark matter comprises over 80% of the universe (Rubin Observatory).

Image: The New York Times

Jennifer Doudna – Dr. Jennifer Doudna’s interest in biology began in Hawaii, where she grew up exploring the islands’ biological diversity. Her father gifted her a copy of The Double Helix, which further ignited her passion for science. Doudna notes that, “In reading The Double Helix, I was captivated by how scientists, working collaboratively, were able to meticulously piece together and solve what had been one of biology’s most elusive puzzles” (“Jennifer Doudna – Biographical”). Upon learning about Rosalind Franklin’s contributions, she felt inspired by the excellence of female scientists and went on to pursue her degree in chemistry at Pomona College while working at labs studying chemical impacts on Hawaiian biodiversity and bacterial chemical signaling throughout her college years. In 1985, she enrolled at Harvard Medical School, where she began exploring relationships between RNA and DNA in Jack Szostak’s lab. Around this time, the Human Genome Project created more “buzz” surrounding research on nucleic acids. As her research continued, Doudna became fascinated by RNA replication and continued it after finishing her PhD in 1989. She worked in Nobel laureate Tom Cech’s laboratory to show that RNA is “able to function as an enzyme capable of slicing, splicing and replicating itself, just as the double-helix structure revealed how DNA is able to store and transmit the genetic code” (“Jennifer Doudna – Biographical”), laying the groundwork for later studies on CRISPR.

CRISPR allows bacteria to store genetic fragments from viruses, enabling them to recognize and destroy future invaders. The system works with CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins, particularly Cas9, to target and cut foreign DNA. Doudna collaborated with Emmanuelle Charpentier, who had been studying how the Cas9 protein worked in Streptococcus pyogenes. Their breakthrough came when they realized that Cas9 could be guided by a synthetic single-guide RNA (sgRNA) to cut DNA at specific locations. This programmable system allowed scientists to edit genes with unprecedented precision. Dr. Jennifer Doudna and Dr. Emanuelle Charpentier won the Nobel Prize for the CRISPR/Cas9 discovery in 2020, revolutionizing technology in molecular life sciences.

Image: U.C Berkeley College of Chemistry

To learn more about the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, visit https://www.un.org/en/observances/women-and-girls-in-science-day.

References:

Sources:

Finding Ada. “Who Was Ada?” Finding Ada, https://findingada.com/about/who-was-ada/. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

Lemelson-MIT Program. “Ada Lovelace.” Lemelson-MIT, https://lemelson.mit.edu/resources/ada-lovelace. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

Lewis, Jennifer, and Dian Schindler. “Dr. Euphemia Lofton Haynes: Bringing a Voice to Black Women’s Rights and Mathematics Education.” Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, vol. 44, no. 4, 2013, pp. 634–661. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5951/jresematheduc.44.4.0634. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

National Park Service. “Dr. Chien-Shiung Wu: The First Lady of Physics.” NPS.gov, https://www.nps.gov/people/dr-chien-shiung-wu-the-first-lady-of-physics.htm. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

National Women’s History Museum. “Vera Rubin.” Women’s History Museum, https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/vera-rubin. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

NASA. “Katherine Johnson Biography.” NASA, https://www.nasa.gov/centers-and-facilities/langley/katherine-johnson-biography/. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

Rosalind Franklin University. “Discovery.” Rosalind Franklin University, https://www.rosalindfranklin.edu/rf100/discovery.html. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

Rubin Observatory. “Vera Rubin.” Rubin Observatory, https://rubinobservatory.org/about/vera-rubin. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

STEM Women. “Women in STEM: Statistics, Progress, and Challenges.” STEM Women, https://www.stemwomen.com/women-in-stem-statistics-progress-and-challenges#:~:text=The%20percentage%20and%20overall%20number,of%20Engineering%20and%20Technology%20graduates. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

SUNY Upstate Medical University. “Elizabeth Blackwell.” Women in Medicine Research Guide, https://guides.upstate.edu/women-in-medicine/elizabeth-blackwell. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

The Nobel Prize. “Jennifer Doudna – Biographical.” NobelPrize.org, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2020/doudna/biographical/. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

The Nobel Prize. “Marie Curie – Biographical.” NobelPrize.org, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1903/marie-curie/biographical/. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

Waters, Jen Rose. “The Pioneering Female Botanist Who Sweetened a Nation and Saved a Valley.” Smithsonian Magazine, 12 Mar. 2019, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/pioneering-female-botanist-who-sweetened-nation-and-saved-valley-180972765/. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.Wexler, Sarah. “Three Quirky Facts About Marie Curie.” Smithsonian Magazine, 4 Apr. 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/three-quirky-facts-about-marie-curie-180967075/. Accessed 9 Feb. 2025.

Leave a comment